Education & Citizenship Blog

Ulisses F. Araujo

Full Senior Professor

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

uliarau@usp.br

This is a reflection and action space, aimed at publishing texts that favor the construction of a more just, solidary, and happy life for each and every being on the planet. Although education is the main reference and personal and collective responsibility are the principles for action, other challenging, complex, and hot themes will be addressed and discussed in this blog. The original texts are written in Portuguese. However, we will add to this English version of the blog a rough Google Translation.

Os Direitos Humanos e as novas cruzadas

Ulisses F. Araujo

07/06/2020

2018 was a special year for the world as it celebrated the 70th anniversary of the promulgation of the Declaração Universal dos Direitos Humanos Site externo (UDHR) by the United Nations. This document became a milestone in civilization's history because it brought to the center of international politics a pact around the rights of each and every human being.

The year of 2018 was especially emblematic for Brazilian society, also because it celebrated the 30th anniversary of the new Brazilian constitution, after two decades of military dictatorship. It became known as the “citizen constitution” for having incorporated into it the legal- principles of the UDHR.

De forma surpreendente para muitos (eu, inclusive), a celebração dupla das conquistas internacional e nacional de garantia de direitos básicos e de luta por uma vida digna para todos os seres humanos, que pareciam consolidadas em nossa sociedade, foi confrontada de maneira direta por discursos de ódio, preconceito e discriminação durante a campanha política nas eleições deste ano no Brasil. O discurso político adotado, que foi vencedor em nível nacional e também nos Estados onde vive a maioria da população brasileira, preconizou e legitimou a discriminação por razões ideológicas, de gênero, de sexualidade, de cor de pele, de origem geográfica, e muito mais, evocando até mesmo a supressão dessas diferenças do convívio social e o uso da violência contra minorias.

Paradoxo do bom cristão

One of the paradoxes experienced at that time, which is already promoting profound repercussions nowadays, is that the prejudice discourses were grounded on Christian religious principles or, we can attest, on the “words” of God in the millennial sacred scriptures. It was hard to understand the perception of these people accepting an intolerant, discriminatory, and violent God, contradictory to the maxims of equality and love of Christianity. In general, these voters when confronted with the paradox showed hesitant responses or got in silence, avoiding to think about it.

Como entender esse paradoxo do bom cristão que aceita e legitima a discriminação, o preconceito e até mesmo a violência, se necessária, para proteger a sociedade? E proteger de quem? A justificativa formal apontava um pretenso ataque perpetrado nos últimos 30 anos por forças políticas organizadas, de esquerda, com o intuito de destruir os valores da família conservadora e tradicional. O propalado ataque envolvia temas caros ao pensamento conservador, como: sexualidade, gênero, machismo, neutralidade educacional, cor de pele, nível socioeconômico, normalização de desigualdades, e outros mais.

Na busca por entender essa situação paradoxal fui estudar algumas das bases do pensamento cristão conservador que vêm se aglutinando no mundo ocidental nos últimos anos, como que unidos em uma nova cruzada.

The power of charity

Let's begin talking about charity, one of the basic virtues of Christianity. Etymologically, the word comes from the Latin caritas, and is defined as an altruistic, individual action to help someone not expecting for any reward. Charity is the main indicator of Christianity's moral uplift, which is highly valued socially and is usually associated with feelings such as forgiveness and guilt.

The feeling of guilt, moreover, as the anthropologist Ruth Benedict showed in 1946 in the seminal book “The chrysanthemum and the sword”, is the moral feeling par excellence of Judeo-Christian cultures like ours. Christian morality, for example, is built around guilt, responsible for psychologically regulating people's thoughts and actions. (for Benedict, shame is the moral feeling par excellence of Eastern cultures).

Better explaining, in Christian cultures, we learn since we are babies, that we should feel guilty when we think or act against values that are dear to us, or when we act "wrong". We learn, then, to take actions that cancel or reduce the feeling of guilt, such as doing charity, forgiving, paying tithing, etc. as a way to recover the psychological harmony and annulate the atrocious feeling of guilt.

In the western cultures we praze Charity, and those who practice it. A person who distributes soup, food to the needed, or helps daycare centers, are highly socially appreciated. Thus, these people live in peace with their personal and social conscience. One possible consequence is that this behavior seems to be sufficient to characterize what is to be a good Christian and a good citizen, giving them social and moral power, allowing them to incorporate criticism toward those who are not considered good Christians. This feeling of superiority may even let them defend publicly punishments for those not considered "good citizens" because are not Christians or at least not the good ones.

The human rights moral logic

The human rights perspective consolidated in the UDHR, however, brought contemporary societies to another logic or moral excellence, grounded in the principles of justice, freedom, fraternity, and equality, culturally inherited from the French revolution. This "new" logic aimed at dignifying life and the social rights of each and every human being. This perspective gives a different moral logic to the public and political dimension, defending that it must be carried out and guaranteed by the State and not necessarily by individuals.

This change in perspective is paradigmatic, and for the past 70 years, it led our contemporaneous societies to accomplish levels of disruptive social and political achievements. One of the most profound changes it causes is in the moral logic of justice, as it recognizes that despite our differences we are all equal in rights. As a result of this social and political dimension, incorporated in most modern constitutions, the State is obliged to guarantee people's rights, such as education, housing, a healthy environment, etc.

In this sense, to exemplify, the State must guarantee to people with cerebral palsy the right to study in a regular school together with all other human beings of their age. And the same principle of guaranteeing equal rights and a dignified life applies to the LGBT community, to colored people, to immigrants, to minorities, to the elderly, and so on.

In this ethical and moral logic based on human rights, it is the role of the State to regulate collective and individual interests. Thus, in the same way, the State has an obligation to regulate traffic and the mandatory use of seat belts to preserve collective interests, for example by fining individuals who do not comply with the law. It is the State's obligation to offer sexual education to young people, teaching them an awareness of the body, affections, and responsibilities. In the same way, because of the goals pursued in just and democratic societies, it is the role of the State to provide a critical education that helps in the construction of values that are opposed to any and all forms of prejudice and discrimination.

Stress nodes

From what has been discussed so far, it is possible to identify some nodes of tension arising from the political and cultural paradox pointed out, which opposes the world of individual charity of the so-called “good Christians” and those desired by the logic of human rights. These tensions have been causing reactions and controversies across the Western world in the past few years and it is not exclusive to Brazilian society.

The first tension in this paradox is the widespread criticism that conservative Christian movements make to the human rights moral logic, attributing such values to the political left. It is known, however, that the French revolution and the UDHR itself are the results of liberal views of society, which have no direct relation to the political views of the left-wing ideas. Thus, there is a dysfunctional discourse in this sense that deserves more attention from everyone.

The second tension, and perhaps the most evident, is the reaction of conservative Christian to the embedded principle in the human rights moral logic that assigns to the State the responsibility to manage norms and customs, often placing the collective interests of society above the individual and family values. This tension is exposed when the logic of human rights is accused of having gone too far by contradicting some ancient biblical texts that prohibit, for example, the theme of sexuality, that recriminate homosexuality, or that negatively emphasize some differences between people. As the world is seen in a dual way by these people (after all there is good and evil, heaven and hell, the family and society), the right and wrong discourse of the good Christian against non- Christians and then the perspective that some differences, such as those of the LGBT community, blacks, poor, northeasterners, disabled people, can be negatively valued.

Charity, in the end, is the other loose end in these tensions. When the State constitutionally assumes the role of guarantor of people's rights and is responsible for reducing social inequalities, it ends up emptying Christian morality and being the target of criticisms of Christian conservatism. For example, when it grants aid or health assistance to certain vulnerable groups. After all, for the conservative Christians, the role of helping vulnerable groups is that of individuals, families, and churches, and not the state, which should not perform such a function.

The new crusades

Concluding this post, what can be observed and reflected, is that we are facing worldwide a conservative Christian reaction against the advance of the human rights moral logic, which carries forward its radical founding principles based on justice and the role of the State as the guarantor of social rights and dignity of life for all human beings.

I understand that more than ever it is time for those who dedicated their lives and their political-social trajectory in favor of social justice to understand the paradoxes of the tensions we are experiencing and to continue fighting so that the conquests of societies in the last decades are not supplanted by partial and conservative readings of the world, which prioritize individual virtues instead of the public virtues contained in human rights principles.

More than ever, it is time to bring the septuagenarian principles of UDHR to the center of the social and educational debate, in favor of building a democratic society that is, really just and solidary.

* Este texto foi publicado originalmente em dezembro de 2018 no blog www.diversa.org.br

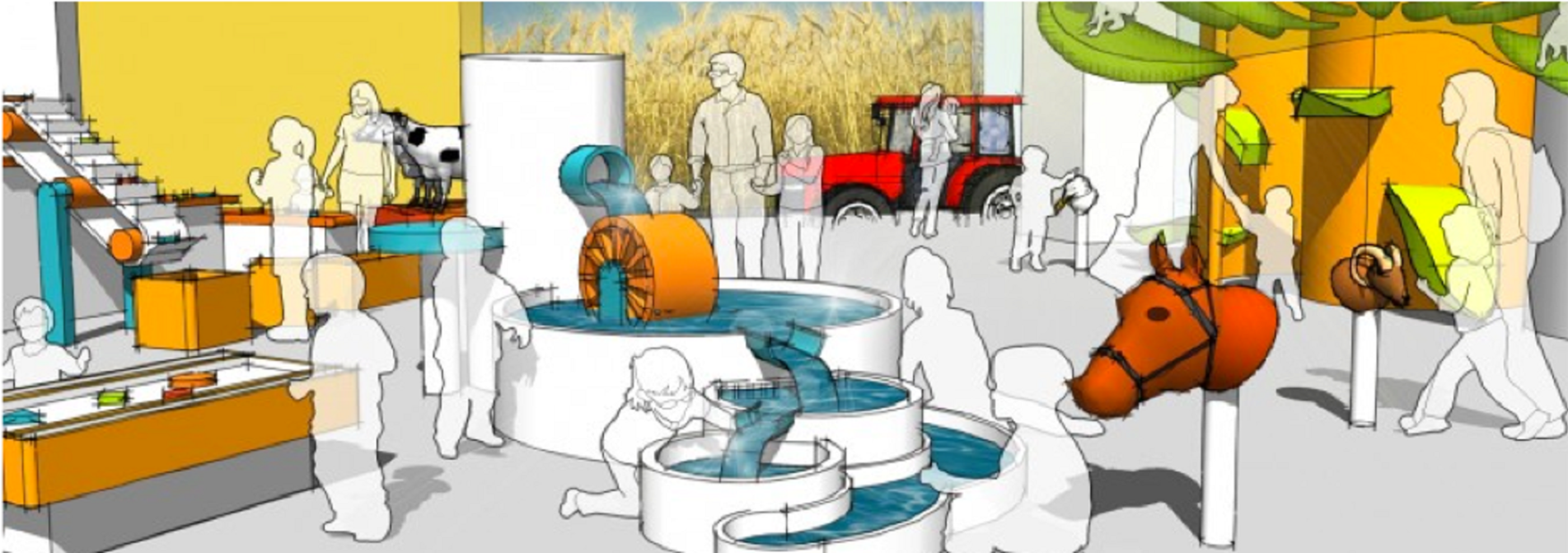

Innovating the Higher Education: the East USP campus

Ulisses F. Araujo

07/06/2020

You can watch below my video-presentation in the Panel "Research for what?", held on 06/01/2020. In the discussion, I present the still innovative 15 years-old campus of the University of Sao Paulo, called School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities. The video is in Portuguese, and soon I will add subtitles in English.